Hiraman | E+ | Getty Images

It wasn’t so long ago that workers had the power to “quiet quit” or join the great resignation. That is no longer quite so easy.

Some laid off employees report they are having a hard time in their job search or making it through hiring processes. In fact, 55% of job seekers have been searching for new roles for so long they feel completely burnt out, according to a survey from Insight Global, a national staffing company. The survey was conducted in July among 501 unemployed adults actively looking for employment.

Workers are feeling the brunt of a labor market that — on paper and to economists’ understanding — is in fact strong. In part, that’s because the broader data doesn’t reflect local trends that come into play.

More from Personal Finance:

What to do if you can’t find an accountant for tax season

Americans can’t pay an unexpected $1,000 expense

Employers and workers are at odds over work-life balance

“A big reason for the disconnect is the unevenness in how different cities and states have recovered,” said labor economist Alí R. Bustamante, deputy director of the Worker Power and Economic Security program at the Roosevelt Institute, a New York-based think tank.

On average, the country as a whole is showing resilience, but some areas continue to have elevated levels of unemployment on top of an increased cost of living, Bustamante said.

Companies aren’t ‘adding staff in great numbers’

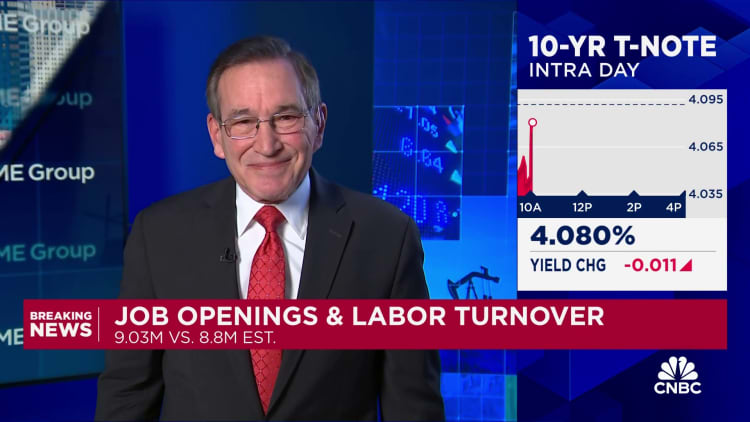

The number of job openings in December was 9 million, a slight increase from November, yet a decline from a series-high of 12 million in March 2022, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in its monthly Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey.

On top of that, both layoffs and hires are at low levels, meaning companies may not be recruiting new workers like once before, said Julia Pollak, senior economist at ZipRecruiter.

Layoffs and discharges changed little at 1.6 million, remaining at a rate of 1% for the fourth consecutive month. Meanwhile, hires in December slightly grew to 3.6%, which is still well below the 3.9% average of 2019, Pollak said.

In November, the hires rate fell to 3.5%, the lowest rate since 2014 outside of the pandemic recession. For all of 2023, the hires rate average 3.8%, making it only the 11th best year out of 23, she said.

“Companies are not growing, expanding, or adding staff in great numbers,” said Pollak. “It’s tricky if you’re a new graduate, for example; not the easiest time to kick start a career.”

‘You would expect job growth would slow’

“As we continue on this road, you would expect job growth would slow because you’re getting closer and closer to full employment,” said Elise Gould, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank. “The reserves of workers are getting smaller because more people have jobs.”

There were more job openings a few years ago because of the high turnover; employers were constantly hiring because employees were frequently quitting and getting hired elsewhere, Gould said.

“There was just a lot more churn and that certainly slowed down pretty dramatically,” she said.

Some states still have elevated unemployment

There are two reasons why the worker sentiment is disconnected from the broader job market data: geography and the “economic trifecta,” Bustamante said.

Some states still have elevated unemployment rates that exceed the national average and are even higher than they were pre-pandemic.

“The reason why this is happening is because states are very different from each other. When you delve in deeper in some areas, you see a lot of variation [in] how communities are recovering … the economic sentiment figures reflect that,” Bustamante said.

From October to November, job opening rates decreased in four states, increased in two, and were little changed in 44 states and the District of Columbia. Hire rates decreased in the sates of Montana (1%), Arizona and Oregon (0.7% each) and California and Connecticut (0.6% each), according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Second, the economy recently hit a “trifecta” across the board of economic conditions that are really strong: The Federal Reserve paused interest rate hikes last July; inflation peaked in September 2022; wage growth reached record highs in 2023.

While these are recent improvements in the economy at large, they aren’t yet reflected in worker sentiment: Wage growth didn’t strengthen consumer’s buying power because of inflation. The Fed’s pause on interest rate hikes will take time to materialize in borrowing costs.

“When you look at the positive news across the board of no more interest rate hikes, inflation is under control and wage growth is still happening … that kind of trifecta has only been around for a handful of months,” Bustamante said.

It will be a matter of time to see the sustained effects of the economic condition in consumer sentiment, Bustamante said.

In terms of national labor data, there is a risk of over-cooling, said ZipRecruiter’s Pollak. Key indicators like quits and hires have deteriorated further from 2019 levels; these measures will continue to decline if rates hold steady, she said.