Mohan is among the mere 5,000 Delhiites who installed rooftop solar power systems under the Delhi Solar Policy, 2016. “I consider the Rs 3.75 lakh I spent on the solar panels a good investment,” said Mohan. “I am not only saving money, but also helping the country’s go off fossil fuels.”

Chief minister Arvind Kejriwal has now announced a new solar policy with more incentives for the people. Even in Census 2011, there were 33,40,538 households in the city. There are more now, but how many of them will be weaned on solar power? Forerunner Mohan wasn’t so sure. “Lack of awareness and the upfront capital cost are things I see holding back many people from their own solar power,” he said.

A few kilometres from Mohan’s home is the sprawling, four-bedroom house of Dr Harsh Awasthi, who got 10kW panels installed at a cost of Rs 5.5 lakh. While his own power bill has slumped to zero, he is unsure about the extra power generated. “What about the surplus power that we don’t require for our house? How can we redeem it,” he wondered, alluding to the lack of clear information on the bill about the power generated each month by the panels, how much is used and how much Mathur has in store.

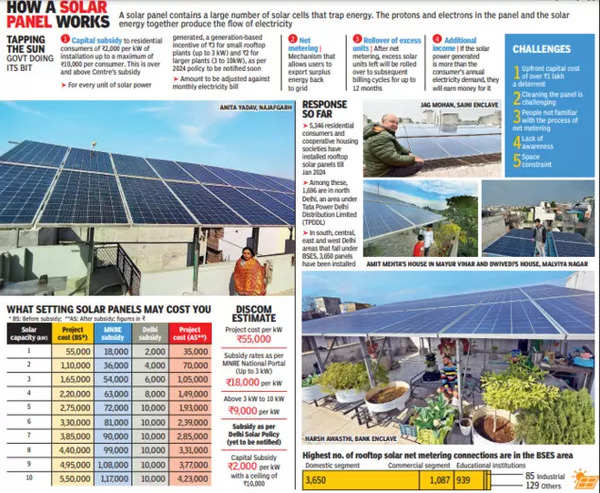

Under the old solar policy, the generation-based incentive (GBI) for residential consumers of Rs 2 per unit conditional to 1,100 units being generated per kW installed per annum. GBI for the surplus power, according to a power distribution company official, is added as balance in the bill, but consumers can claim the amount and have it transferred to their bank accounts.

Anita Yadav, who lives in Najafgarh, earns around Rs 30,000 yearly as GBI with her 5kW plant that she installed in 2019 for around Rs 2.5 lakh. “Most of our electric appliances have a five-star energy efficiency rating, so we are able to save a lot of energy,” she explained.

The net metering mechanism allows users to export their surplus energy to the grid and be paid for it. The 2016 policy allowed one to get the payment twice a year, but the 2024 policy makes a monthly claim possible.

Both Mathur and Yadav said the only inconvenience in having solar panels was the need to keep them clean. Depending on the dust, it is necessary to clean the panels once or twice a month, said Yadav. Mathur said, “The dust sticking on the panel slows down energy production, so someone has to climb to the roof and clean it with soap water. This should be part of the annual maintenance contract.”

Delhi’s sunny weather helps generate enough units every day for investors to recover their installation costs in a short time. Prakash Dwivedi, a govt employee, put up 5kW panels for Rs 1.5 lakh at his Malviya Nagar home in 2019. “Since the installation was in the near winter month of November, the power generation was a bit low,” he said. “But by May-June, we were producing enough not to have to pay any more for electricity.” He recovered the cost in a year and a half, describing the input as a “recurring deposit”. The only time Dwivedi encountered a problem was when two of his panels fell during a storm and he had to spend some money to have them up again.

IT professional Amit Mehta used to pay around Rs 8,000 a month for his electricity consumption. After putting up 5kW panels in his Mayur Vihar I house, for which he spent Rs 2.3 lakh, he pays just Rs 2,000 a year, mostly when the generation goes down in winter to around 18 units from the 25 in summers. “But even that amount was nullified by the Rs 4,000 BSES paid me last year for surplus energy. So it was rounded off,” he said happily. “One other benefit is that putting up the panels shades the top floor from being heated up,” Metha added.

The life of a solar panel is around 25 years, so one can save a lot of money in the long run. A govt official said that the people’s concern about the upfront capital cost could be alleviated by the RESCO (renewal energy service company) model, only that vendors haven’t shown much interest in domestic setups. “But in future we will tweak the model,” the official said. In the RESCO model, people have zero investment, with the solar plant installed by a vendor. The vendor signs a power purchase agreement with the house owner who gets electricity at subsidised rates, while GBI is paid to the vendor.